Perspective taking: a clever tool for reframing design problems

“To solve your toughest problems, change the problems you solve”.

This quote from the cover of Thomas Wedell-Wedellsborg’s book, What’s Your Problem, may sound like a cop-out; if you can’t solve a problem then just change the problem. Too simple, you say? I think what Thomas is really saying is, “don’t judge (define) a problem by its symptoms”.

In this article, we take a deep dive into one strategy for framing a problem; perspective taking.

How do we design the right thing before designing it right?

As designers we aspire to design the right thing before we design it right. From experience, the best way to do this is to deliberately check-out different framings of the problem before launching with the one presented to you. Thomas offers us a few strategies to do this.

- Looking outside the frame.

- Looking in the mirror.

- Re-thinking the goal.

- Looking for bright spots.

- Taking their perspective.

He recommends picking and choosing your strategy (as not every strategy is applicable to every problem), but always applying the last one – Taking their perspective, as it will give you a deeper understanding of the stakeholders impacted by the problem. This strategy, however, should be applied as a last strategy, so that one is not trapped into a singular perspective of the problem.

Pick and choose your strategy as not every strategy is applicable to every problem, but always apply the last one – Perspective Taking

What is taking their perspective?

‘Taking their perspective’ is all about trying to experience the problem from the perspective of each stakeholder, identified as impacted by the problem. On first reading you may think of this as empathy and turn to the trusted design tool Empathy Mapping. However, perspective taking is much more. “Perspective taking, in comparison, is a broader, more cognitively complex phenomenon in which you aim to understand another person’s context and worldview, not just his or her immediate emotions.”1

Effective perspective taking will help us go from merely imagining ourselves in the users’ shoes to imagining users in their own shoes so that we become better attuned to their problem perspective.

Making perspective taking effective

Is empathy enough?

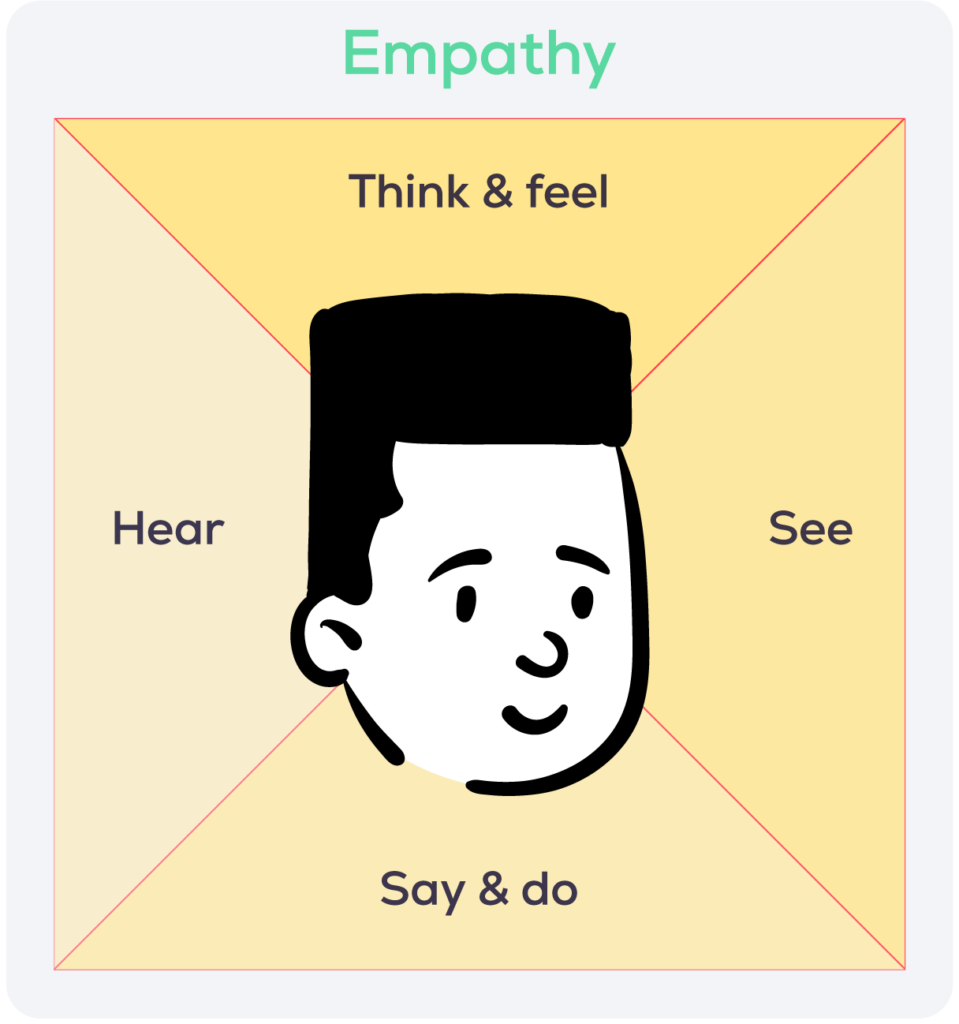

Empathy is a good place to start perspective taking – but is it enough? Empathy is broadly defined as your ability to feel what someone else is feeling. Empathy mapping has been a favoured go-to tool for problem solvers and designers to understand our stakeholders holistically – finding out through various research methods what they say and do, and extrapolating the information gathered to imagine what they might think/feel, hear and see.

Paul Ekman2 the famed psychologist, identifies three forms of empathy used in responding to another person’s pain, two of which are relevant to us as problem solvers and designers.

- ‘Emotional empathy’ is “where you feel what other people feel as though their emotions are contagious”. It helps us attune to the inner emotional world of another. This is what designers hope to achieve through empathy mapping3 – seeking to better understand the emotional experience of stakeholders as they face a specific problem.

- ‘Cognitive empathy’ sometimes referred to as ‘perspective taking’ is “simply knowing how the other person is feeling and what they are thinking.”4 This ‘knowing’ can help designers understand the motivations and negotiability of stakeholders in presenting solutions designs.

How to achieve that illusive ‘knowing’?

Thomas agrees with the famous behavioural economists (and key re-framing thinkers) Daniel Kahnemann and Amos Tversky that effective perspective taking has two parts to it.

- Anchoring – The process of empathy mapping is, in effect, the anchoring part of perspective taking, which naturally leads us to ask, “How would I feel in that situation and what might be my response?”. The danger of stopping with anchoring is that we all respond differently to a situation and so predicting our responses may not always unearth the problem perspective of our stakeholder or help us design the solutions required to solve the stakeholder’s problem.

- Adjustment is the second part of perspective taking. It is to “adjust away from your own preferences, experiences and emotions asking, ‘How might they [stakeholders] see things differently from me?'”5. For example, if I were my best friends, I’d be excited at the thought of flying to Paris for my big birthday bash. But I know some of them are strapped for cash, so maybe somewhere cheaper would be their preference.

Overcoming the challenges of adjusting away from ourselves

Adjusting away most certainly is a deliberate act on our part. It will require some focused energy to rise beyond our own emotions and opinions and escape the entrapment of our own perspective. There are two simple techniques that will help us adjust away from ourselves.

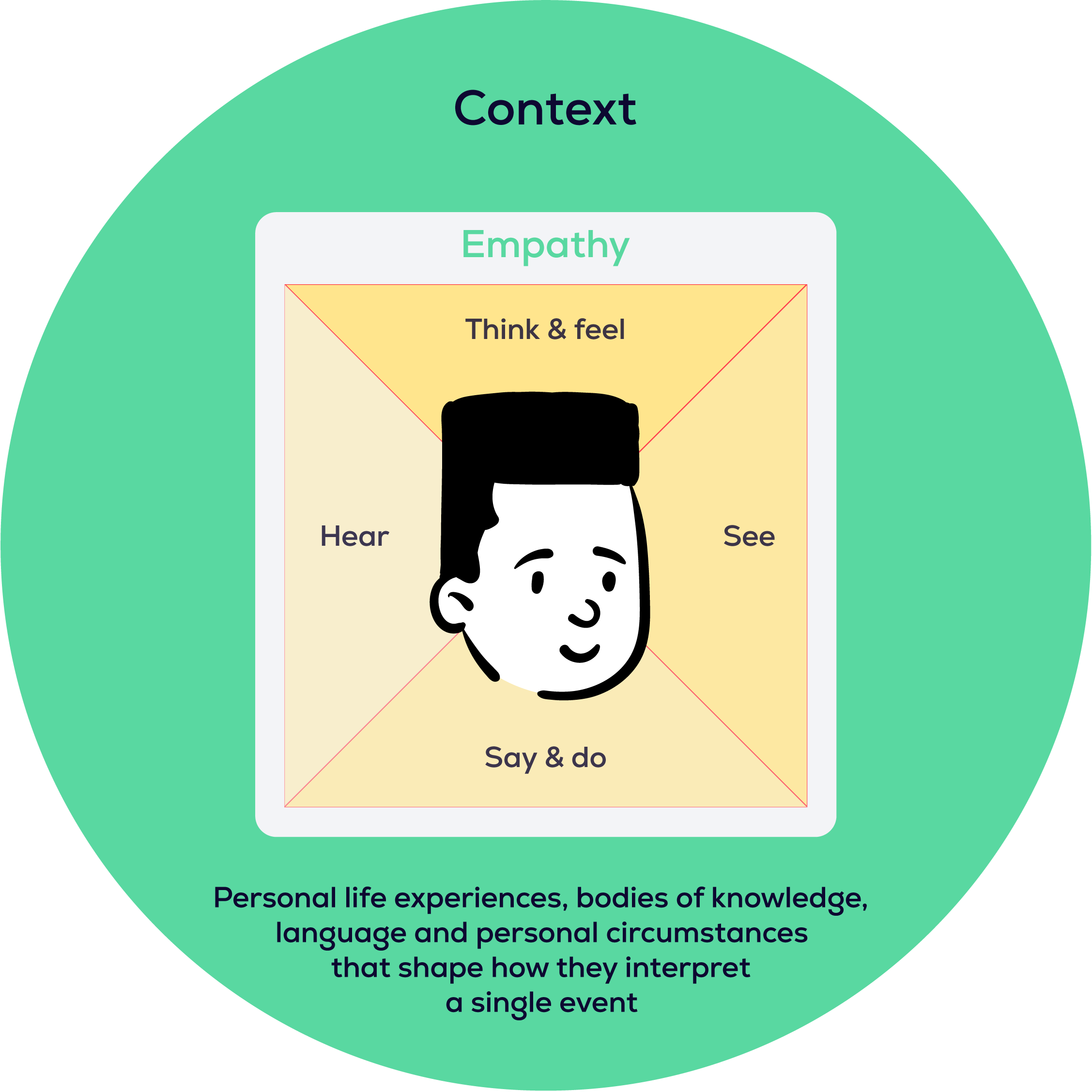

Adding Context

Context is the lens through which we view our immediate problem, goal or need. The context in which someone experiences a problem not only impacts the way they interact or respond to that problem but also changes the perspective of the problem. To complicate matters, context may not remain fixed over longer time frames but is prone to change as circumstances change.

“Sometimes your greatest strength can emerge as a weakness if the context changes” 6

Harsha Bhogle

Cricket commentator, presenter and journalistFor example, when performing user research that would inform the design of a new service portal, we discovered that the key pre-implementation obstacle to success and high adoption of the new portal was not its design or how well it met the needs of employees (though that would eventually be a major contributing factor), but it was the organisation’s historical record of change management. A long history of failed technology roll-outs due to poor planning, communication, and training had impacted user perceptions and attitudes towards ‘yet another roll-out’ of new technology. Understanding the context helped us read the results of user research more accurately and address this in solution design.

Understanding the context helped us read the results of user research more accurately and address this in solution design.

Context impacts the behaviour, motivation, decision making and problem perspective of a stakeholder considerably. Some example contextual factors include:

- Past life experiences

- Past interaction experiences with similar products/services

- Channels of interactions

- Disabilities

- The journey of the stakeholder to current point of interaction

- Motivational factors

- Short term goals

Adding Worldview

Adding the worldview in which the user operates, adds yet another deeper layer of understanding, of how a user experiences and perceives a problem.

A Worldview is a view of the world, that influences the way we interact with and live in the world. In practical terms this includes what is judged as good or bad, desirable or undesirable in terms of objectives, behaviours, relationships and even goals that can be pursued. It is the stakeholder’s mental model of reality.

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” 7

Anaïs Nin

NovelistResearch suggests that human cognition and behaviour are powerfully influenced by our set of beliefs and assumptions about life and reality. As problem framers and designers, our understanding of stakeholders’ worldviews can help us frame the problem sympathetically so that our solutions are strategically designed.

Our understanding of stakeholders’ worldviews can help us frame the problem sympathetically so that our solutions are strategically designed.

Key Takeaways

Whilst anchoring activates emotional empathy (empathy mapping) and is the first step in perspective taking, the addition of adjustment activates cognitive empathy to enable a deeper knowing of our stakeholders.

Whilst one can never fully ‘know’ what another person is feeling or thinking, or adjust away from our own perspective, the ability to do so is considerably enhanced by coming to a deep understanding of the context and worldview in which another person is saying, doing, thinking and feeling.

Our best chance of designing ‘it right’ is to know we are designing the right thing. Using techniques discussed above gives designers the opportunity to frame problems closer to the perspective of the stakeholder. The effort of active perspective taking – anchoring and adjustment – is well worth the effort to ensure you are framing the problem right and designing strategic solutions.

Want to know more?

At Sitback we use behavioural science to understand our client problems and their customers’ behaviours so that we can design the right things right. Contact Sitback’s team of XD experts and registered psychologists to find out more!

References

1Wedell-Wedellsborg T 2020, p 114

2Paul Ekman is a psychologist ranked 15th among most influential psychologists of the 21st century and one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time Magazine.

3Empathy maps were originally created by Dave Gray a Design Thinker

4Daniel Goleman renowned psychologist and author of the 1995 book Emotional Intelligence

5Wedell-Wedellsborg T 2020, p 117

6Harsha Bhogle Quotes. BrainyQuote.com, BrainyMedia Inc, 2022. https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/harsha_bhogle_559641, accessed September 9, 2022

7Anais Nin Quotes. BrainyQuote.com, BrainyMedia Inc, 2022. https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/anais_nin_107089, accessed September 9, 2022.